Leica M-D: Review and First Impressions

Tired of pressing buttons by mistake? Fed up scrolling through endless lists of jpeg settings you are never going to use? Discouraged by digital bloat? Always feeling your camera is out of date, with a new bobby dazzler just arrived at the local dealer?

If so, you are not alone. But the new Leica M-D (Typ 262) could be just the digital camera you have been waiting for. No buttons to press, whether deliberately or otherwise, no endless menus (because there are no menus), updates few and far between.

I've had the M-D in my hands for the past 72 hours and have run around 600 test shots to get familiar with the handling. For an experienced M240 user, the M-D is business as usual. It performs just like the M but shoots only RAW files, as we know, and has the simplest possible set of controls.

Although it weighs exactly the same 700g as the M and M-P and shares all major dimensions, this camera feels slightly smaller and more comfortable than the parent cameras. This is an illusion created mainly by the flat, featureless back and the lack of buttons. But it does feel different.

DESIGN

General styling of the camera is similar to that of the M-P, with an unadorned central screw head above the lens instead of the Leica logo. The top plate carries the familiar Leica script logo and "Leica Camera Wetzlar Germany", again identical to the M-P. On the back of the top plate is the engraving “Made in Germany”, missing from the M-P.

The top plate, which is made from brass, has a small step on the left hand, similar to that of the old M9 and the new M262. It is made possible by the removal of the microphone found on the M and M240.

The small thumb rest to the right of the back incorporates a thumbwheel which is used in set-up functions and to adjust exposure compensation. Finally, right in the middle of the plain expanse of the rear is a chrome circular dial for ISO adjustment.

CONTROLS

This is the simplest digital camera you could imagine. It takes around a quarter of an hour to learn everything there is to know.

Controls are sparse in the extreme, little different from those of a film camera. The shutter speed dial is identical to that on its sibling cameras—a fastest speed of 1/4000s and an A position for aperture priority. With A selected you can choose the aperture and the camera will set an appropriate shutter speed. The main switch on the top plate is identical to that on all Ms, with positions for single-shot, continuous and self-timer.

Near the main switch is a small chrome function button which is dedicated to a select set of functions. This is the selfsame button that engages the video mode on the M and M-P. On those cameras I always had it disabled but it now has a real use.

Unlike the M240 and M262, the M-D features a frameline lever enabling you to preview alternative sets of framelines without needing to change lenses. This is similar to the arrangement on the M-P model.

The most obvious of the few controls is the large chrome ISO dial in the centre of the camera back—just where you would expect to find it on any M from the M3 in 1954 to the M7 or M-A in 2016. On earlier cameras this served the purpose of an aide memoire to indicate the loaded film. On later cameras equipped with exposure metering it offered the ability to adjust sensitivity in accordance with the film.

On the M-D the ISO setting is a simple dial showing values between 200 and 6400 in 1/3 stops. There is no auto ISO. I thought I would miss this (it is something I use by default on the M-P) but this direct access to a clearly marked ISO scale is very usable. I found myself easily switching from the standard 200 to a higher setting when necessary, such as indoors). It's just a matter of remembering to set it back again afterwards, but this will become a matter of habit. The dial is beautifully precise and perfectly damped, easy to move with one finger but not loose enough to be moved inadvertently.

The beauty of this dial, despite its retro pretensions, is that it constitutes a vital third side of the exposure triangle: Aperture, speed and ISO. It really is very straightforward and totally satisfying to use. Nothing could be easier. I could envisage the M-D becoming an essential tool for teaching photography. If it weren't so expensive, of course.

VIEWFINDER

Normally I wouldn’t spend too much time on the viewfinder of an M camera. In this case, though, the finder is the fount of all knowledge. No menus, no screen, so everything is accomplished by a set of red LEDs at the bottom of the finder window. They are at first cryptic but ultimately familiar and informative. After a weekend with the camera I am now feeling quite pally with the functions.

In the viewfinder, the sole control display of the M-D: 1) Framelines in bright LED-illuminated white; 2) Focus patch; 3) Digits to denote all other functions. Simple.

Bright electronic framelines are presented in sets of two, depending on the lens in use or the position of the front-mounted frameline selector lever. The pairs are 28 and 90mm; 35 and 135mm; and 50 and 75mm. This is standard fare from the M240 except that there is no red colour option; white is the default. Again, as with the absent auto ISO function, this frugality is down to the impossibility of adjustment without a menu.

The framelines are linked to the range setting of the lens to compensate for parallax effect; again this is normal M camera practice and nothing new.

In aperture priority mode the red digits indicate the auto-matically selected speed. In manual exposure mode (when a specific speed and aperture is user selected) the display presents two opposing red triangles with a central red dot. The left and right triangles indicate the direction of movement needed in either the aperture ring or speed dial to approach correct exposure. When this is achieved the central red dot illuminates. This arrangement is familiar to users of M6TTL and later film cameras and is also a feature of the M digitals.

In normal operation you need remember only the status check. A quick prod of the function button brings up the number of frames left. However, since only three digits appear to be available for use, you will see 999 until the card capacity falls below that figure (approximately 24GB of remaining storage), at which point the countdown will begin. By way of experiment I just inserted an old 1GB card and the display shows 26 shots remaining. It's interesting to ponder on using such small cards, either 1GB or 2GB because it recreates the restrictions of film. Would you be more careful in composing and shooting if you knew the card would be full in, say, 36 shots (to pluck a figure out of the ether).

With large cards, therefore, it is difficult to tell how many frames you have shot until you get home and open Lightroom (unless you have a small card taking no more than 1,000 files). A 32GB card is a happy medium and will shows 870 shots available and the countdown will be visible. I was using a 64GB card, hence the 999 constant display.

A second prod of the function button indicates battery charge in red digits representing a percentage. Thus, 100 tells you the battery is fully charged and there is then a countdown to zero The red digits also provide all the less obvious information from the camera. There are coded displays to indicate various functions or malfunctions. These include Sd (card missing, not compatible), Full (memory card full), bc (battery empty), UP (firmware taking place or completed), Err (firmware update not possible). It’s a bit like going back to a Casio Digital Assistant in the 1980s.

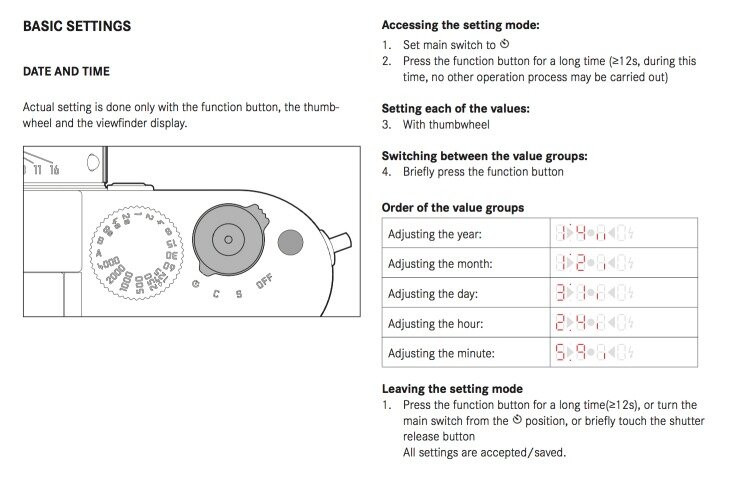

The function button, on the top plate to the right of the main switch, also serves to help with date settings and firmware updates. All functions are indicated by means of red digits in the rangefinder.

HANDLING

This camera handles exactly as the M or M-P, with the same weight, size and overall familiarity. It does differ in one important way, however. The smooth back, devoid of buttons and protrusions, is a delight—it is a tactile triumph and I immediately felt right at home. As you walk down the road, the camera snug on its wrist strap, your fingers can fondle that smooth derrière and revel in the unaccustomed sensuality. It is so refreshing after all those buttons which offend the fingers and just beg to be pressed by mistake.

Taking photographs with the M-D is very familiar territory for experienced M shooters. You have a choice between manual exposure, choosing aperture and speed, or semi-automatic aperture priority. Just like any digital M or, indeed, just like the M7 film camera. If you have used any M camera, whether film or digital, you will feel right at home.

The overwhelming impression given by the M-D is one of simplicity, purity of purpose and intelligent implementation. I don't expect a majority of photographers to think it's a good idea but it will appeal to an important niche of Leica enthusiasts.

The only other available option is exposure compensation which is adjusted by holding down the function button and turning the rear thumbwheel. The digital display shows compensation in the range of ±3EV in 1/3EV steps. After the compensation has been set the value is shown every time you half press the shutter release. This is a good reminder to prevent mistakes.

The shutter mechanism is claimed to be much quieter, presumably in relation to the M but on par with that of the M262. I don't notice a great deal of difference but the shutter is definitely very sweet and subdued. It is quieter than the M-A and M3 Adam Lee and I had out on test yesterday and, overall, this is a very discreet and unthreatening camera. I've used it for street photography on two days over the past weekend and it is a natural, only one little step away from a film camera.

Other than those red digits in the viewfinder there is no indication of what is happening, no confirmation you are doing the right thing. It all comes down to faith, as it does with film. However, there is one little clue that this is not a film camera: In the bottom right hand corner of the back is a hidden LED which lights red to indicate when the camera is writing to disk or otherwise busy. With the slower 1GB buffer of the M240 (in contrast to the M-P’s 2GB) this camera isn't going to break any speed records when it comes to continuous shooting. It is good for two frames per second but after about six frames the buffer is working hard and things slow down. Subjectively, though, it writes faster than I imagined and I was not conscious of any deliberate restrictions on my shooting.

The camera has no adjustment for sleep time. The exposure meter is switched off after about 12 seconds and the camera is then said to be in stand-by mode. A quick press of the shutter button and the display and meter come to life almost instan-taneously. I wasn’t conscious of a delay on waking, as is the case with most digitals, and the speed is more akin to using a film camera—pick up and shoot. I’m not sure about this but it just feels super fast. I imagine that the electronic functions are so limited that the processor has to handle far fewer lines of code to get up to speed. Subjectively, however, the camera feels faster than the M or M-P.

A quick word on white balance. Since the camera saves data in compressed loss-free DNG format, white balance is automatic and cannot be adjusted.

What more can I say? This stripped-to-the-bones digital really is a film camera with a digital back. It won't suit everyone; it delights me.

LENSES

There is no means of selecting lens profiles, but settings for six-bit-coded lenses (that is, all modern M lenses) are baked into the firmware. The camera identifies the lens name and focal length which is then embedded in the metadata.

Uncoded lenses can be used successfully and, of course, the camera then identifies only the focal length. In the absence of in-camera processing, I doubt that the lack of coding will be a hindrance. The camera worked perfectly with my 1963 50mm rigid Summicron, for instance.

Leica says that, in general, most M lenses can be used, whether or not the lens is coded. If it is coded, the camera uses the information transmitted to optimise exposure and image data. However, even without this identification, the camera should deliver excellent pictures in most situations, according to the instructions manual.

The manual contains some warnings and restrictions on the use of various older lenses (including the dual-range Summicron, which must not be used) and collapsible lenses (which in general must not be collapsed while mounted). The two Tri-Elmar lenses need a special mention. The Medium Angle Tri-Elmar (MATE) features mechanical transfer of the focal length to the camera, which is necessary to set the framelines, and this allows the lens information to appear in the EXIF data. This applies to both versions of the MATE. With the Wide Angle Tri-Elmar (WATE), on the other hand, the focal length is not transmitted to the camera and the values do not appear in the EXIF data.

SD CARD FORMAT

One odd omission from the M-D is a card format function. However, it is just a matter of doing this on the computer rather than in the camera—when necessary that is. I think many of us fall into the habit of frequently formatting a card when inserting it into the camera, as much to clear existing data as anything. In fact, though, formatting is not necessary every time and, when it is required, is easily accomplished on the computer. The only thing we need to remember is to delete the old files before pulling the card out of the computer. This can be done automatically with some PP software, including the latest Lightroom, but I prefer to do it manually to be on the safe side.

PROCESSING

Since the M-D produces only DNG files some form of post- processing software is essential. Out-of-cameras files, although brimming with embedded detail, are flat and uninteresting. I use Lightroom and it is possible set up a basic profile to adjust files to your general preference as they are imported. Inevitably, though, my keepers are worked on to a greater degree.

There is no owner/user information available from the camera, it is just like a film camera in this respect, but you can add copyright and other metadata in Lightroom.

BATTERY LIFE

With a jumbo battery designed for the profligate video excesses of the M240, this frugal snapper should have the staying power of a camel. Could it have the best battery life of any digital camera ever made? Even on the M240, with live-view disabled, the battery life is remarkable. It isn't unusual to get 750 shots out of a battery. So I had high expectations for the M-D, although these were not immediately realized.

Today, on the second day of shooting, with a freshly charged battery, reserves dropped almost immediately to 90 percent but then stuck there stubbornly for an hour or two. Then the descent began, but slowly. I had 166 shots in the can at the end of the day and the battery check was still reporting 75% power remaining.

I could extrapolate this to 665 shots per charge, but I won’t. Life will certainly improve as the battery settles down and I would not be surprised to be able squeeze 1,000 shots out of a full charge. I will run the current battery, with its 75% remaining charge, into the ground and then calculate the number of shots. But optimum performance is not achieved until the battery has been fully discharged and recharged several times.

CONCLUSION

Apart from the delight I take in handling and using the M-D, I have a fair conviction that this is one digital camera that will last and last. Sure, the M240 sensor may be coming to the end of its life (the SL and Q both have an improved version) but the sensor in the M-D is good enough for purpose. The M-D will not need many of the improvements that will come with a new sensor—in particular higher ISO performance since it is limited by the physical design of the camera to the 200-6400 range. There is so little room for improvement—restricted, I would say, to more megapixels (if you want them, I don't particularly) and a faster processor (again of doubtful value in this camera)—that I can see it becoming something of a classic.

If it takes good photographs now (it does), it will still take good photographs in ten years' time, just like a film camera. Even the M9, with its "antiquated" CCD sensor, low ISO performance and silent-movie screen still takes good pictures. Indeed, the M9 has had something of a revival and I know several photographers who have gone back from the M240 and M246 to the M9 and M9 Monochrom. Leica users are a funny breed; and the M-D has been specially bred for them.

Already I have two friends, who have purchased the M-D. That makes three of us, at least, in the first weekend. I hear that dealers' phones have been busy since the announcement. I am reminded of the launch of the Monochrom when it was roundly criticized for offering less for more money (I seem to remember £6,000 being the original price). Yet it was a great success for Leica and, surprisingly, has not been copied by any other manufacturer. In this sense, Leica is the only manufacturer still prepared to break the digital mould. And, make no mistake; break it they have with the new M-D.

I absolutely adore this camera after only two days. I am prepared to make it my default rangefinder because it is just so right for me. The SL and other digital cameras can massage my technological alter ego when I feel I have the need. But when it comes down to horses for courses, this M-D is the nag I'm going to like, particularly for street photography.

All photographs in this article (other than the Leica product shots) were taken with the Leica M-D and 50mm Apo-Summicron ASPH. All on the same day, 1 May 2016.