Real Cuba

In 1959 Fidel Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos, and Che Guevara successfully overthrew the Batista government and took over in Havana. Back in Indiana, in 1959, my mother gave me my first camera. She challenged me to go out and make photographs that were “classic”. I asked her, “What kind of photographs are classic”? She said, “That’s for you to figure out”. I spent 1959-1961 with my camera in the basket of my bicycle, riding all over our small town, looking for photographs that were “classic”. The American cars of the 1950’s became intriguing subjects for me, as did everyday life on the streets of our small town. Although I didn’t realize what I was doing, in fact, I was documenting life around me in my small hometown.

In 1961, an intruder entered our home and shot my father, critically wounding him, and also shot and killed my mother. My world was turned upside down. In the aftermath of the shooting, I went to live with my maternal grandparents. In the midst of the immense grief, all of my photographs and my cameras were lost forever. After that day, whenever I saw a camera, all I could think of was my mother. And so I didn’t touch a camera for a long time.

It took forty years for a camera to seriously find its way back into my hands. In 2001 I was newly divorced and I decided that I had to try and pick up a camera once again. Analog photography was rapidly being impacted by digital photography, and so I bought a digital Nikon D50 DSLR. I worked my way through several digital DSLR’s, including a Nikon D70, Nikon D300, and then a Nikon D3s. I was learning the nuances of digital photography, but somehow the magic just wasn’t returning.

One night I happened to watch a video by Konstantin Adenauer of Germany, entitled “Craig Semetko: A Portrait”. Semetko was using a Leica rangefinder camera, something that was foreign to me, but intriguing at the same time. Soon I had purchased a copy of Craig’s first photo book, “Unposed”. As I studied his photographs, it felt like I was being transported back to my childhood, looking at my mother’s black-and-white photographs. I loaded up my Nikon D3s, all my Nikkor lenses, and traded them for a Leica M9 Rangefinder camera and a 50mm f/2 Summicron lens. In a very short period of time, I realized I was beginning to find the little boy with his camera in the basket of his bicycle once again. The magic of the Leica M9 and a 50mm lens helped me find me again, and my photographic journey began again in earnest.

I rediscovered my love of simply documenting life as it happens around me, always striving to find that “classic” moment that my mother had challenged me to find. For some reason, using a Leica rangefinder instead of a DSLR had helped me find my photographic vision again. The Leica rangefinder with a prime lens forced me to work more methodically, and when I worked more methodically my vision improved. The prime lens made my legs do the work instead of simply relying on a zoom lens. Shooting the M9 with its 50mm lens in many ways was similar to using my first Kodak Brownie Camera and later my Imperial Satellite 127. When I converted my M9 digital files to black-and-white, I was mesmerized. It was as though I had come full circle from my childhood forty years ago.

The opportunity to travel to Cuba for eight days in the spring of 2018 presented itself and I was thrilled at the thought of stepping onto Cuban soil. My equipment had comfortably settled into two cameras and two lenses: a Leica M240 with a 28mm Summicron ASPH and the Leica M Monochrom 246 with a 50mm APO Summicron ASPH. I always carried both the M240/28mm Cron and MM246/50mm APO around my neck together. With those two focal lengths, I was instinctive in terms of which focal length I needed for the shot. The long battery life on the M240 and MM246 allowed me to simply have both cameras on at all times – so it was a quick reach for the right camera, touch the shutter lightly to refresh, and I was ready to shoot. On narrow, cobblestone streets, I usually set my M240/28mm Cron up to use zone focusing. Depending on the light, I usually had my ISO set to around 800 or 1000, my aperture to f/11, and with my focus ring set appropriately, everything from about 1.2 meters to infinity was in focus. I used my MM246/50mm APO in settings that weren’t so confining, or when I chose to do a tight portrait. My methods were occasionally unorthodox -- I sometimes shot through the window of a bus as we traveled from one location to the next. In Santiago de Cuba, I captured a shirtless truck driver apparently deep in thought. Life happened fast, our time was short, and I didn’t want to miss a moment.

To me, documenting Cuba meant documenting the people. Since I believed that photographs of Cuba were quickly becoming a cliche, I was convinced that my work in Cuba was to capture real life. Much of what I saw, even from some famous photographers, had oversaturated colors and scenes that appeared to be candid but almost certainly were posed to look as though they were candid. Therefore, I set out to capture beautiful moments of people immersed in daily life, in black-and-white, which is where my roots in photography have always been.

As is typical in Cuba, life spills from the homes directly onto the streets, almost as if there is no separation between the private and public spaces. I encountered serious games of dominoes, sometimes on the street in a residential area with four people sitting quietly around a table, and sometimes downtown in the public square with crowds of people clamoring around the table. In Baracoa a little girl’s eyes twinkled as her mother watched her adoringly from their terrace. Not far away, a grandmother lazily leaned against her doorway. Her smile and the wrinkles in her face reminded me that life is precious and fleeting.

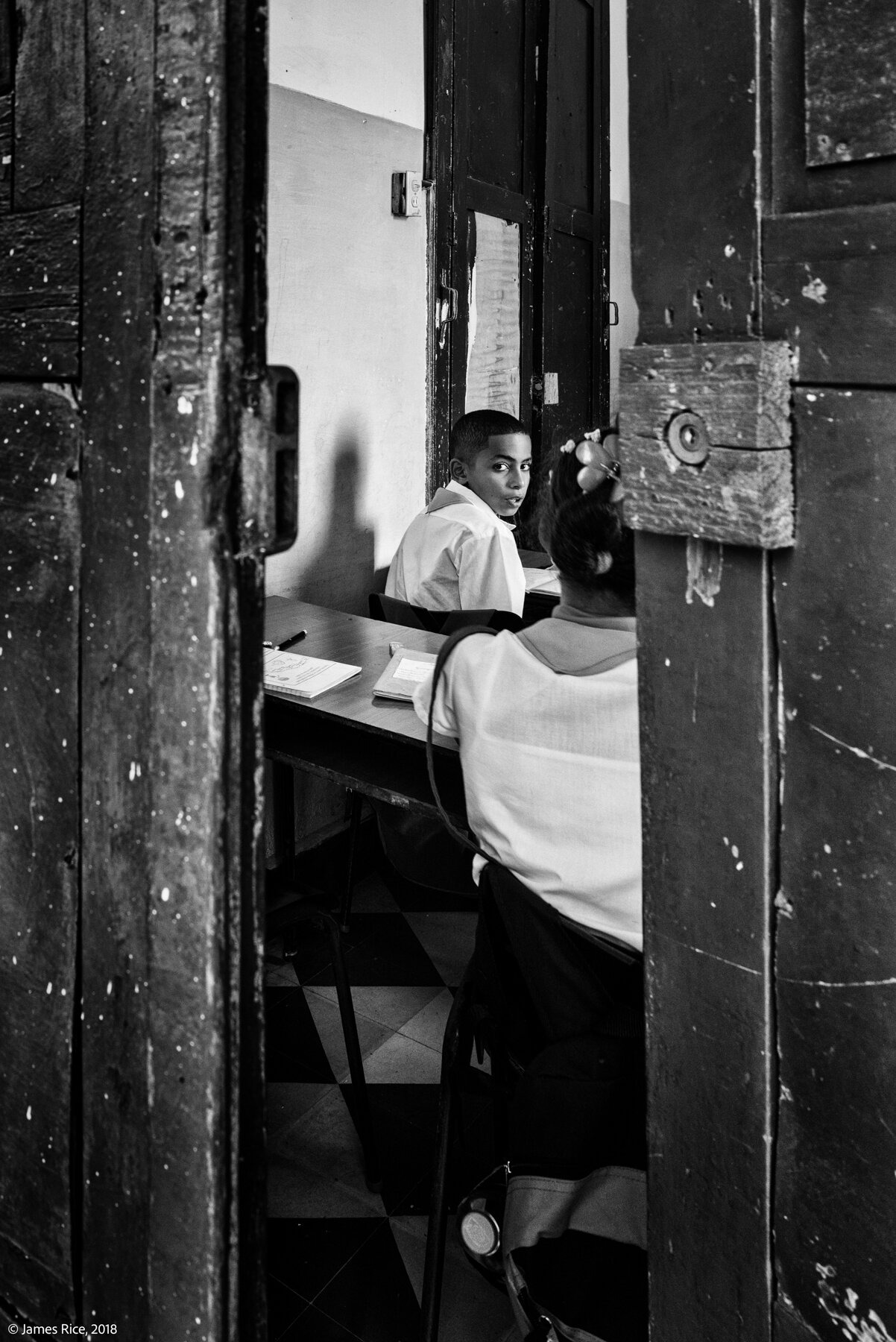

Downtown, a young boy in an elementary school glanced over his shoulder and peered at me through a well worn wooden door. Not far from the school, on the steps of city hall, an apparently homeless man shared his sandwich with his two dogs. As I walked along a side street, an old man with a baggy shirt and a heavily wrinkled forehead grinned and spoke to me from a step he was sitting on. For a moment I didn’t see a partially obscured man just inside a doorway behind him, sitting shirtless in a chair. The man on the step was cordial and talkative, but the man in the chair was silent and wary of me. Such is life.

As a young boy, my first experience in my hometown barbershop in the mid-50's was magical. When the men in our Cuba entourage spied a barbershop in Baracoa, it was a done deal that we would all go in and get a haircut. The minute I stepped in, my mind raced back to the 1950's and I was that little boy again, thrilled to be in this place. Thrilled because this place was still stuck in the 1950's. There was the pedestal sink, crusty trashcans, the noisy fan, hair clippings all over the floor, and the open windows to the outside. And all the while I was turning back the calendar pages and once again becoming an excited, inquisitive little boy. I was again reminded that at 65 years old, I'm still as inquisitive as I was as a little boy. My Leica cameras are my portals to another world that isn't limited by time and space – they take me to surprising places when I least expect it, and when that happens, I do my best to click the shutter at just the right time.

I discovered that the light and shadows in Cuba were spectacular. When I was in Baracoa, I spotted a man riding in the shadows of a bus. Through the open window, I could only see the lower half of his face, and in his left hand, he held a ticket. In Santiago de Cuba, I was mesmerized as two women wearing polka dot headscarves stood in heavy shadows over a steaming pot, making some of the best espresso I have ever tasted. Not far from Santiago de Cuba, at the Gran Piedra Botanical Garden, a woman tucked away in the shadows used a makeshift broom to sweep a walkway, while a chicken pranced in the sunlight behind her. In Havana, an old man wearing a safari hat, glasses perched on his nose, and cane tucked under his arm, read from a small notebook to a man with his hands impatiently planted on his hips, the sunlight casting a long shadow in front of him. A third man, rather sinister looking, standing in the shadows, appeared to be disinterested. On another side of Havana, I glanced up to see a woman standing on a balcony, half of her face lit by the sun, half hidden in the shadows. As she stood behind the wrought iron railing, her expression left me wondering what was going on in her life.

Not far away, I turned a corner and happened to look to my left. Deep in the shadows of a decaying building, a father was teaching his young son how to box. The textures of the walls, the rickety iron stairs, and the tenderness of this moment once again reminded me that nothing is more beautiful than real life.

One afternoon in Havana, I noticed an old Chevrolet parked along a narrow cobblestone street. As I walked closer, I realized the car wasn’t meant to be my subject. As I knelt down to compose the photograph, I paused for a moment – there was so much to see. Beyond the Chevy, a young woman with her hand to her head stood with noticeable style and grace, a small purse hanging from her shoulder. Beyond her, the Spanish architecture of the majestic buildings glistened against a relentless afternoon sun, and a bird soared slowly in the warm skies. Only a few blocks away, in a residential area, I came across an old man sitting on a step in front of padlocked doors. Next to him, his faithful dog seemed to stand guard. In real Cuba, life doesn’t need to be posed or contrived, rather it simply needs to be seen and appreciated.

Near the end of my journey in Cuba, I visited Cojimar, a small fishing village east of Havana. This village had been the inspiration for Ernest Hemingway when he wrote The Old Man and the Sea. High on a hill I discovered an abandoned building sitting in a state of severe decay. It appeared to be an old hotel. Two ornate stone columns with lights on top held an old wrought iron gate. As I made the photograph of this place, there was both great beauty and sadness in what I saw. That was a rather frequent sentiment I felt while traveling in Cuba. The more I thought about that, it occurred to me that there is both great beauty and sadness in life, for all of us. As I walked away, I knew I wanted to embrace both the beauty and sadness, for all of my days.

James Rice is an Indiana-based documentary photographer. His roots in photography go back to the days of black-and-white film in the late 1950’s, and the bulk of his work remains in black-and-white to this day. All photographs were made with either a Leica M Monochrom 246/50mm APO Summicron ASPH or a Leica M (Typ 240)/28mm Summicron ASPH. James traveled to Cuba with Complete Cuba, a travel company based out of Chicago, focused on allowing small groups to experience a broad range of the entire island experience. Our group visited Holguin, Santiago de Cuba, Baracoa, Havana, and the countryside in between those places.

James and his wife Dona reside in the Arts & Design District of Carmel, Indiana. His work can be found as follows:

www.jsricephotography.com | www.facebook.com/jsrice00 www.instagram.com/jsrice00 | www.flickr.com/photos/jsrice00

James has published two books, “Second Look” and “Chicago Avenue”. Both are available at blurb.com and also at www.jsricephotography.com.